A window into Foundations for Discovery

MS2 Global Health Equity Pathway students embarked on first-ever Foundations for Discovery.

This fall, a cohort of MS2 Global Health Equity Pathway students embarked upon the first-ever Foundations for Discovery experience. During Foundations, students spend a minimum of three weeks at a partner site to meet potential mentors and key stakeholders, learn about the political, historical, and structural determinants of health at the site, and begin to develop a longitudinal project for their Discovery Year. GHP interviewed three members of the Fall 2022 cohort—Nafisa Wara, Xochitl Longstaff, and Kate Holland—to find out more:

Tell us about your Foundations experience.

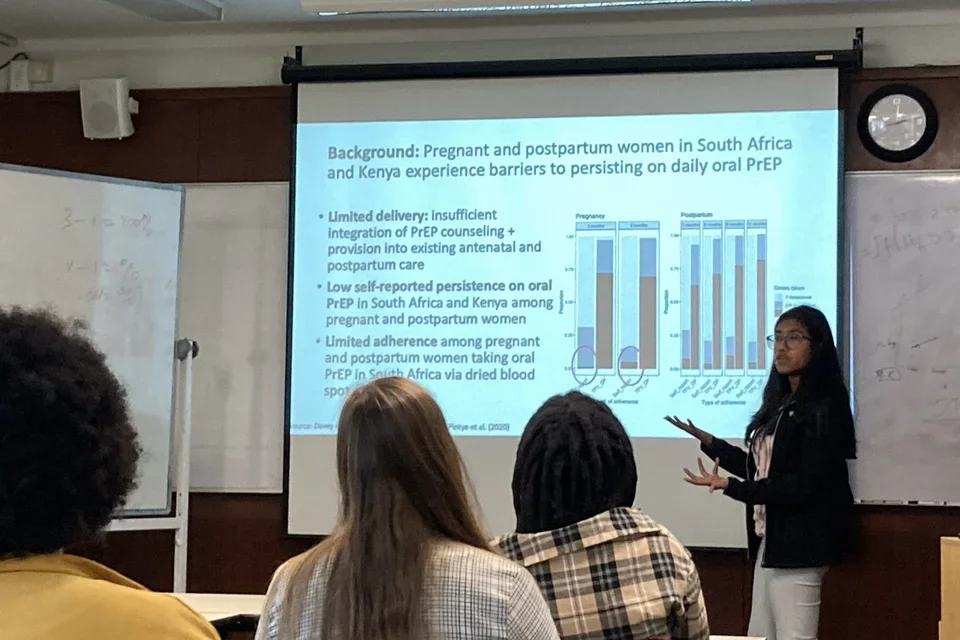

Nafisa: I spent my Foundations time in Cape Town, South Africa, working with Dr. Dvora Joseph Davey and her team at the University of Cape Town and Gugulethu Midwife Obstetrics Unit (MOU), a clinic for pregnant and postpartum women in Cape Town. I have been so lucky to be collaborating with this team along with Dr. Risa Hoffman here at UCLA since June of 2021, so it was honestly really exciting to finally meet in person so many people whom I have become so familiar with over Zoom! Our research is on long-acting PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), which is a medication someone can take to protect themselves from HIV transmission. Currently, the most commonly available type of PrEP is a daily oral pill. There has been exciting research over the past couple of years (led by Dr. Landovitz here at UCLA) supporting the development of injectable cabotegravir, a long-acting PrEP injection that only needs to be administered every 8 weeks, is even more effective at preventing HIV than the PrEP pill, and may be an easier-to-use alternative for some people who have difficulty taking a pill every day. I was curious to understand the perspectives of women in South Africa on long-acting PrEP compared to oral PrEP—particularly those of pregnant and postpartum women, who face unique challenges in accessing HIV and sexual healthcare—and so we have collaborated on developing implementation science studies exploring this question.

Xochitl: I learned a lot during my Foundations experience with Refugee Health Alliance (RHA) in Tijuana, Mexico. The situation in Tijuana is constantly changing, so even though I started working with RHA in 2019, it is always a humbling experience to return and learn the latest nuances of the political/humanitarian crisis at the border and the organization’s new workflow. The demographics of patients in the clinic also shift over time. Currently, over half of the patients seen in the clinic are from Haiti. While the clinic has recruited Haitian-Spanish interpreters, I left my Foundations experience inspired and determined to learn some basic Haitian Creole to better communicate with our Creole-speaking patients.

Kate: I am currently working on a project with Dr. Kate Dovel focused on treatment interventions for people living with HIV in Malawi who have disengaged in care. The project chiefly focuses on men, because they have not been the focus of large-scale HIV implementation science projects and thus have not received adequately-tailored services compared to other individuals living with HIV. In Malawi, men are typically considered the breadwinners of the home and thus spend a lot of time working outside of the home. Much of this work is migratory work, and so men are living a busy and nomadic lifestyle. HIV clinics can be very hectic and the long wait times are just one of many reasons that there is difficulty retaining men in care.

Was there a particular incident that gave you insight into the cultural context and/or unique needs of your site?

Kate: Much of my time in Malawi was spent coding interviews between intaking psychosocial counselors and people living with HIV who fell out of care. Through these interviews, I learned about myriad reasons people couldn’t continue with treatment. One that came up again and again was migratory work that resulted in people needing to cross the border into Mozambique and other countries. People would often end up staying longer in-country than their supply of anti-viral medications could support. While “health passports” exist to allow Malawians to pick up their HIV medications at clinics across Malawi, the passports don’t work outside of Malawi. This was particularly interesting to me, as many clinics in Mozambique are also working with PEPFAR and other multi-national donor funds, and thus the idea of denying an individual life-saving treatment funded by an outside non-country-based source seemed like a problem that shouldn’t exist. I think this is something that large-scale donors could certainly work to alleviate and would help minimize the number of treatment dropouts we see, ultimately saving many lives.

Xochitl: One challenge that Refugee Health Alliance faces is the continuity of personnel. The weekday clinic is run by a consistent group of providers. However, Saturday shelter visits often have new providers and volunteers each week. It can be a challenge to ensure that everyone is properly trained on the tools and protocols of the clinic every week. For example, there have been times when the volunteers assigned to triage have not been trained to use the clinic's glucometers, which caused problems because diabetes is a common issue in the patient population that the clinic treats. Similarly, antibiotic stewardship is important to RHA, but hosting many volunteer providers with different backgrounds and thresholds for prescribing antibiotics makes it difficult to ensure that standard/best practices are always employed.

Nafisa: I noticed a lot of vocal interest in long-acting PrEP methods from pregnant and postpartum South African women enrolled in our study; multiple times women asked us, “When will the PrEP injection be available?” This also was reflected in some data that we have already collected and analyzed: of 190 pregnant and postpartum women surveyed in Cape Town who have used oral PrEP at some point in their past, three-quarters of them would be interested in switching to a PrEP injection rather than staying on oral PrEP.This was a sobering reminder of how important it is to keep pregnant and postpartum people at the forefront of access to HIV prevention moving forward, particularly in a context like South Africa where one in three pregnant women is living with HIV. Of course, there is a necessary caution in offering a new drug to someone pregnant or breastfeeding because of the impact it may have on the fetus or infant. However, pregnant and postpartum women in South Africa and other contexts could potentially benefit from accessing a safe, long-acting method of HIV prevention. This is an incentive to pour more resources, time, and money into investigating those safety questions early, so that if a form of PrEP like injectable cabotegravir is safe to use during pregnancy and postpartum (as indicated by preliminary safety data thus far), pregnant and postpartum women in South Africa can access it as soon as possible.

How did the Foundations experience shape your plans for your Discovery Year? Was there something you learned that you don’t think you could have learned at home?

Nafisa: I learned an immense amount from being in Cape Town for Foundations, particularly from spending my days observing and learning from clinic nurses and staff at the Gugulethu MOU. It’s clear through our work thus far that there is a lot of interest among pregnant and postpartum women at the clinic in injectable PrEP, once it is available. I realized that we need to think hard about how to integrate these multiple types of PrEP that may be available soon into an antenatal clinic setting. And of course, the best way to learn about how to integrate PrEP into antenatal care is from the experts themselves: the clinicians and clinic staff providing care in the clinic and the women who are patients there. I’m planning to explore these issues through a health systems lens during my Discovery Year, and I truly can’t wait.

Kate: It allowed me the time to engage in a series of smaller research projects that paved the way for the ultimate capstone project I will be working on with the team in Malawi. While in-country, I got to really dive into the data surrounding the use of client-centered, male-specific, and motivational interviewing style of care, and how these different methodologies work for clients and help to bring them back into treatment. All of this lays the groundwork for the project I ultimately plan to work on with Dr. Dovel during Discovery Year, where we want to focus on how to take these research-proven concepts from the boutique to the standard of care in Malawi and beyond. Without this dedicated month-long period, I don’t think I would feel even half as knowledgeable about the barriers to care faced by Malawians and the ways in which these interventions can work to reduce that burden of disease.

Xochitl: It solidified my desire to work with RHA during my Discovery Year. One of my personal goals for Discovery Year is to build clinical research skills. I found that approaching any clinical research work in an international non-profit setting comes with unique challenges. However, these challenges are also excellent learning opportunities. I learned a lot through the process of exploring possible projects with RHA, navigating difficult questions such as how to choose a research project that will truly benefit the patients we serve, how to conduct ethical data collection when working with a vulnerable patient population, and how to balance managing the day-to-day needs of a busy clinic that serves migrants with a longitudinal project.

Is there anything you would do differently during Foundations if you had the opportunity to do it again?

Nafisa: I spent a lot of time with the chronic medicine nurses at the clinic who provide PrEP to patients at the clinic. Next year I’d love to spend more time with other providers within the clinic as well, to really understand what someone experiences when seeking care during pregnancy and postpartum, regardless of whether they want to access HIV prevention.

Xochitl: I would try to get more exposure to all the different services RHA provides earlier in my month there. Since RHA hosts multiple visiting volunteers, the team is very good at quickly training and incorporating new volunteers into the clinic workflow. From day one as a volunteer, my days were quite busy triaging patients, helping manage the pharmacy, and performing administrative/documentation tasks. While I was grateful to feel useful, it did make it more challenging to explore other areas within the clinic. When I requested to spend my last week working with the midwives, everyone was very supportive and agreed. I wish I had asked earlier so I could have worked with the other specialties in the clinic as well.

Kate: I think I would have tried to learn some Chichewa before coming. Everyone told me not to worry and that Malawians speak English most of the time anyway, but despite the widespread use of English, I felt like there were certain scenarios when knowing some Chichewa would have been useful or gone a long way. For example, all the exciting gossip and joking seems to be done in Chichewa! Nevertheless, a sweet woman named Irene took us under her wing and started to teach us the basics of the language. I know for sure, though, that when I come back for the year I will be studying up on my Chichewa.

Learn more about the Global Health Program Pathway and Foundations for Discovery Programs on our webpage.